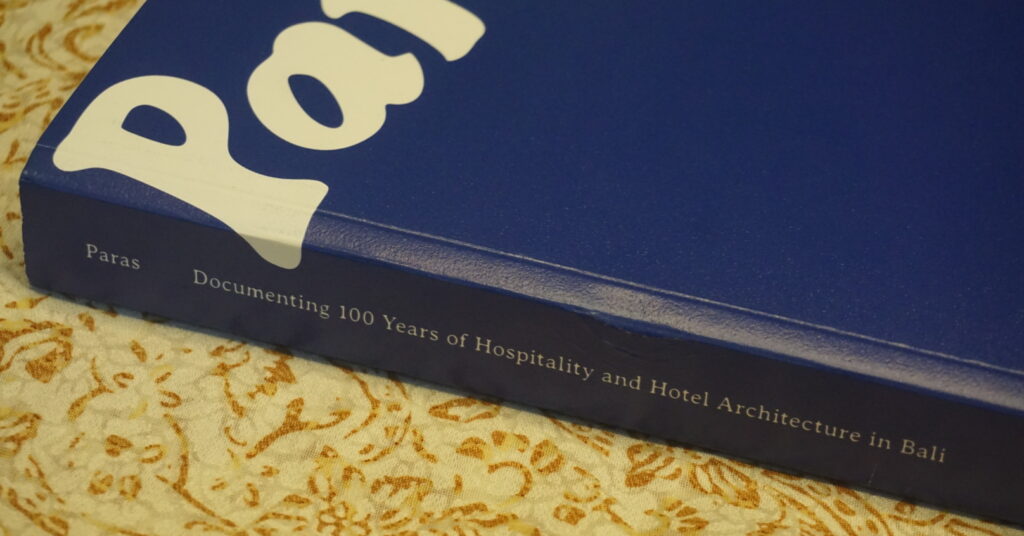

“Paras”: Celebrating 100 Years of Balinese Hospitality and Hotel Architecture

Beyond its touristy slogan as “The Island of Gods,” the Bali island of Indonesia is where a complex interplay of culture, spirituality, nature, and design happens. This intersection is explored by Radit Mahindro, author of Paras: Documenting 100 Years of Hospitality and Hotel Architecture in Bali. In this installment of Creative Spotlight, EnVi spoke online to Mahindro about what drives him to document Balinese hospitality and hotel architecture, and also his vision on the island he calls home.

About the Author

With a career spanning fifteen years in the hospitality industry, Radit Mahindro has held key roles at prominent Asian brands, including Kayumanis, Regent Hotels & Resorts, Alila Hotels & Resorts, Potato Head, and Aman. His expertise also extends to consulting for independent hotels like Soori Bali, Tandjung Sari, and Nirjhara, as well as environmental organizations such as Begawan and Space Available. During the COVID-19 pandemic, Mahindro co-founded Paras, a digital platform, with Balinese art curator Krisna Sudharma to document the evolution of Bali’s tourism and hospitality sectors. The book, Paras: Documenting 100 Years of Hospitality and Hotel Architecture in Bali, is a direct expansion of this digital initiative.

Paras: Documenting 100 Years of Hospitality and Hotel Architecture in Bali began as a personal writing project without a formal curation process. “I wrote it during the pandemic, not in chronological order, but based on historical discoveries,” Mahindro says. Preparing it for publication involved reorganizing the material and conducting interviews with sixteen key individuals involved in Bali’s hospitality scene.

Answering “Why Bali?”

To Mahindro, Bali’s global significance in hospitality and architecture stems from its distinctive yet receptive culture and landscape. “Bali captivated a wide array of individuals — colonial authorities, presidents, artists, surfers, and more — who each responded to the island in their own architectural language,” he explains. This results in an eclectic mix of structures that reflect personal visions shaped by Balinese traditions.

Over the past hundred years, Bali’s hotel architecture has changed dramatically. Initially, architects and designers sought to express the island’s culture outwardly. “But in the new millennium, the trend has reversed,” says Mahindro. “Outside influences are brought in, often by architects with formal training but perhaps limited understanding of Bali itself.” This has led to a proliferation of high-concept, globally inspired spaces — many of which feel detached from the island.

Early Days of Balinese Hospitality

Mahindro mentioned that the hospitality scene in Bali has undergone a few significant changes. “Previously, it centered on welcoming familiar faces — family and friends — into private homes or intimate guesthouses like Campuhan, Poppies, and Tandjung Sari. These interactions were built on existing relationships and shared interests, resembling genuine friendships,” he explained. However, today’s hospitality industry is vastly different, moving from personal connections to a focus on accommodating strangers and travelers. The relationship between owners, operators, and guests is now primarily transactional, with little to no prior bond between them. This profound change over the last century is the result of several intertwined factors, including postcolonial transitions, political shifts, government regulations, industrial investment, and even acts of terrorism.

The early signs of Balinese hospitality dates back to the 1930s. The 1931 International Colonial Exposition in Paris was a crucial turning point for Bali, introducing its unique culture to a global audience. This exposure was particularly effective thanks to its charismatic spokesperson, Tjokorda Gde Raka Soekawati, who not only engaged with European journalists but also personally orchestrated the island’s captivating dance and music performances.

Just five years later, his influence continued as he co-founded the Pita Maha art movement, a precursor to today’s artist-in-residency programs. It was this powerful blend — a highly distinct Balinese culture, the welcoming nature of the local people, and the strategic image-building efforts of the Dutch colonial government — that first captured the world’s imagination in the 1930s. This potent combination laid the groundwork for Bali’s enduring global appeal.

The Genesis of Bali’s Image

According to Mahindro, the Dutch colonial government initially presented Bali as an exotic and enigmatic island, populated by mystical tribes known for their intricate craftsmanship in both clothing and architecture. This narrative was developed amidst rising nationalism across Asia, Africa, and South America, prompting colonial powers to adopt a facade of protecting indigenous cultures. Interestingly, Bali itself was somewhat detached from this burgeoning nationalist sentiment, which had already spread through Java and Sumatra, and was largely unconscious of its unique cultural identity.

The launch of the weekly KPM steamship, however, marked a turning point. With direct links to numerous Dutch East Indies port cities (Batavia, Surabaya, Makassar) and Singapore, Bali began receiving visitors from a wide array of disciplines and backgrounds. These newcomers extensively documented the island through journals and photographs, consistently expressing deep admiration for its culture, nature, and, notably, its friendly and welcoming inhabitants. This favorable impression was, to some extent, facilitated by the Dutch Baliseering policy, which aimed to preserve Balinese culture as a positive initiative, helping to reconstruct their image after the devastating massacre of thousands of Balinese in the early 1900s.

How Balinese Architecture Shaped the Works of Architects

Essentially, an architect working on a project in Bali does not impose their vision on the island’s architectural language; instead, Bali profoundly shaped their designs. The core motivation is to create spaces that are both enjoyable and comfortable by thoughtfully responding to Bali’s unique climate, landscape, and rich culture. This approach means that architectural and visual styles, including the scale, building materials, and construction techniques, are heavily inspired by the island itself. This leads to a series of hospitality establishments that powerfully convey a distinct sense of place, a sense of being distinctly Balinese. What also stands out is the dedication of these visionary designers and hoteliers to first deeply study Bali. For instance, Peter and Carole Muller are renowned for their numerous volumes documenting traditional Balinese design and architecture, a feat echoed by Made Wijaya, who authored even more.

Further, according to Mahindro, the design of a hospitality shape inherently shapes the guest experience. A mega-resort with over 300 rooms, for instance, often struggles to deliver truly genuine service. In contrast, an open-concept space like Potato Head fosters a communal and informal atmosphere. He notes that while luxury international chain hotels provide exclusivity, they can feel rigid due to their strict operational guidelines, whereas home-like establishments like Amandari and Tandjung Sari offer intimacy and familiarity. “I believe the relationship between design and hospitality is a universal principle. Ultimately, the very architecture and interior design of a place dictate, and are in turn dictated by, the style of hospitality it offers,” Mahindro states.

The Heart of Balinese Design & Destinationism Over Tourism

Mahindro wrestles with a profound question at the heart of Balinese design: What defines Balinese identity? “Is it the carved entrance gates, alang-alang roofs, or red brick walls?” he muses. Culture, he argues, is always evolving — yet outsiders often expect it to stay frozen in time. “How can Balinese culture evolve without losing its essence?” It’s a question with no easy answer, but one he believes is crucial to ask.

While many new developments in Bali claim eco-consciousness, Mahindro points out a critical oversight: cultural sustainability. “We see energy-efficient buildings that could exist anywhere in the world,” he says. “They miss the nuanced cultural fabric of Bali.” In his view, true sustainability must go beyond engineering — it should also consider the local culture, people, and their relationship to place.

Perhaps Mahindro’s most compelling concept is “destinationism” — a mindset that prioritizes the well-being of the place and its people over visitor-centric planning. “Tourism has made us forget that Bali is a home, not a theme park,” he says. Mahindro argued that many of the island’s growing pains are directly tied to a tourism-first mentality.

“I find the term ‘tourism’ inherently tourist-centric, a definition readily confirmed on Merriam-Webster’s website. My fifteen years experience in the hotel industry have left me fatigued by conversations centred on tourism plans, strategies, marketing, and indeed, anything to do with tourism. Having lived in Bali for thirteen years, I witnessed firsthand the hardship the island faced during or even before the COVID-19 pandemic, including a severe water crisis, rampant overdevelopment, significant waste management issues, and irresponsible tourist behaviour,” Mahindro says. He further emphasizes that this “tourism-first” mentality leads to the expense of the native Balinese people.

Mahindro believes that the primary concern should be the basic needs of all local residents within a region or destination, extending to its animal and plant life. This includes ensuring access to clean air, soil, and water, along with adequate health and safety, education, transportation, and the freedom to move. These fundamental needs, in his view, should take precedence over the continual push to attract more tourists and build additional infrastructure primarily for the tourist’s benefit.

A Hope for the Future

When asked how he hopes Bali’s hospitality industry will evolve over the next 10 to 20 years, Mahindro answers with: “Refocus on hospitality, not hotels, and on destinationism, not tourism.” His hope is that travelers, designers, and hoteliers alike will take a more conscious approach — one that respects the island’s rich history while embracing sustainable progress.

Paras: Documenting 100 Years of Hospitality and Hotel Architecture in Bali is available to purchase through their website. Also, tune in to their Instagram account for more insights on Balinese hospitality and architecture!

Looking for art exhibitions in Bali? Check out EnVi’s piece on illustrator Gusde Sidhi’s exhibition: Tales of Spice Memories here!