Tram Anh Nguyen on His Debut Solo Exhibition “Hoa” and Grieving the Lost Words of His Bà Nội

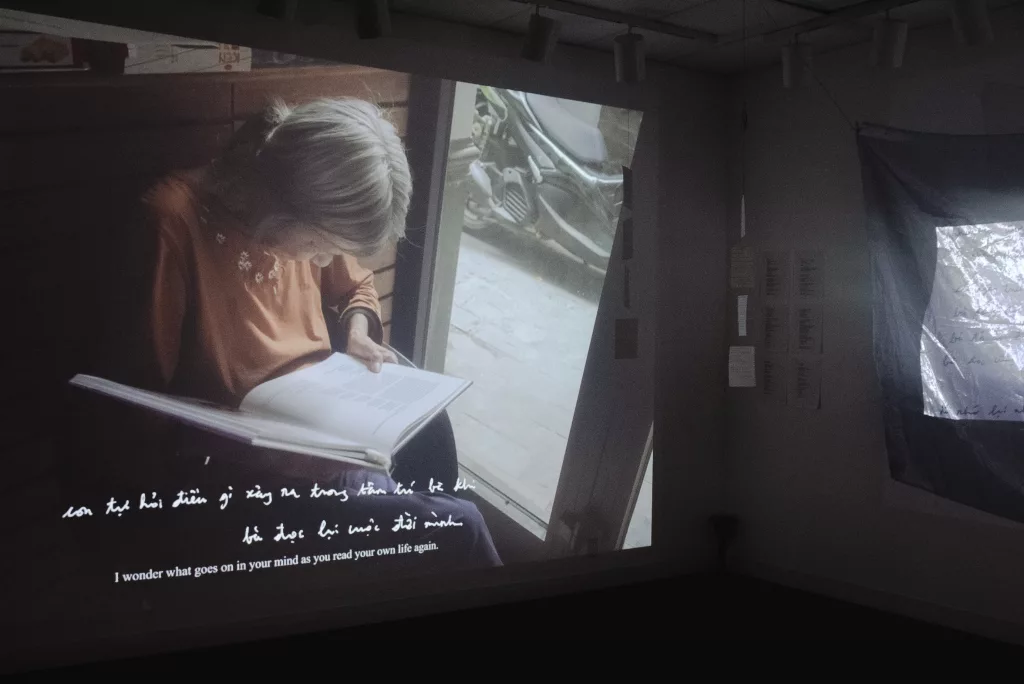

Screened onto a darkly lit room, the words dedicated to Tram Anh Nguyen’s grandmother were projected over a series of photographs: “Bà Nội, my father’s mother, I hope the last time I see you won’t be the last. Do you miss me?” he narrated in Vietnamese. Images lined the walls of the surrounding area as attendees circled around to closely observe. Conversations filled the exhibition space as attendees resonated with Nguyen’s grief. But somehow, “Hoa” offers a universal experience for all. One for Nguyen, which captivates hope for the Vietnamese diaspora, and another for viewers who identify with collective grief.

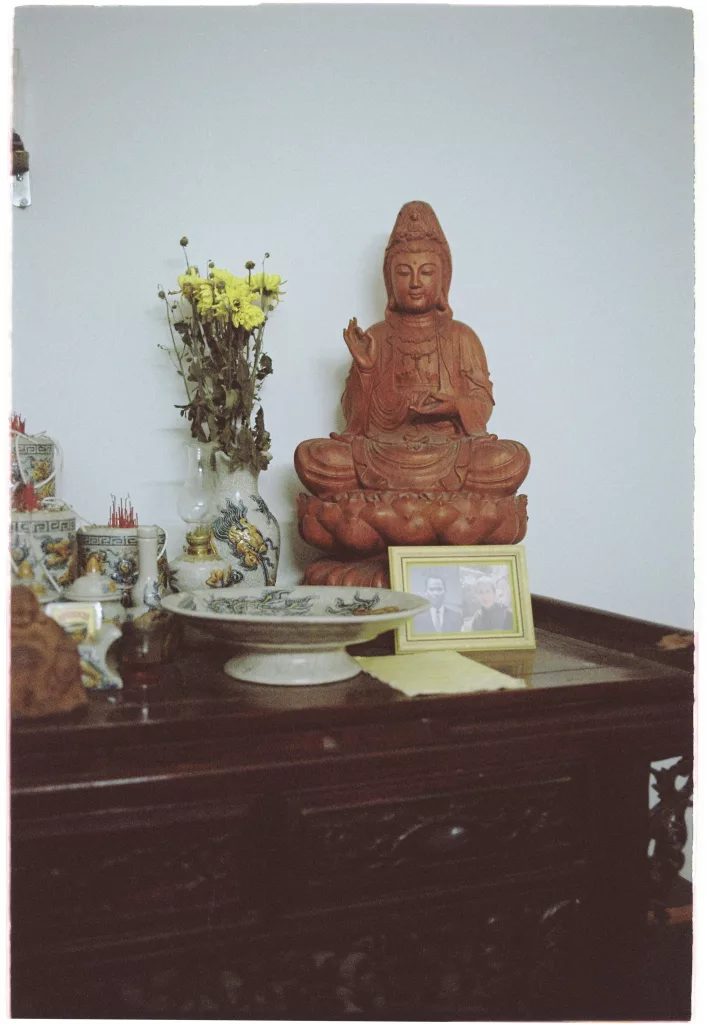

Nguyen’s first solo exhibition at Toronto Metropolitan University’s Image Arts Centre, titled “Hoa” (2022) from February 27 to March 10, combined a series of analog and digital photographs, film, and poetry. In the form of visual and written letters, Nguyen dedicated the body of work to his paternal grandmother, Hoa. He remains inspired by the name of his grandmother — which translates to “flower” — in all aspects of the exhibition. Upon returning to Vietnam after three years in Canada, he captured the ordinary, strenuous tasks of his Bà Nội. Shot over the summer of 2022 in Hanoi, Nguyen took on many different roles as an observer.

The sounds of students walking in and out of buildings ran familiar to Nguyen as he sat against a white chair in the comfort of his campus. Around midday when students were finishing classes or frantically returning back to campus newsrooms, Nguyen confidently took a seat with EnVi to further dissect the importance of “Hoa,” his first solo exhibition, and his Vietnamese identity.

A Letter to Bà Nội

Before developing her memory disorders, Nguyen’s grandmother, Trần Thị Tuyết Hoa, wrote an autobiographical book about her life titled Hồi Ức Tuyết Hoa: Khi Đất Nước Tôi Thanh Bình: Hồi ức của một nữ sinh viên Sài Gòn (Memories of Tuyết Hoa: When My Country is Peaceful: Memoirs of a Saigon Female Student). In an attempt to regain memories of her life, she now reads this book every day in her Hanoi home.

To retain the memories given by his grandmother, Nguyen curated “Hoa” with his own perspective as a Vietnamese grandchild in mind. Like many immigrants, stories from the motherland remain untold with time, but this project sought to shape a moment of learning. Thus, Nguyen collected the remnants of his grandmother’s life through her books and other photographs.

“This film was more of a letter to her and all the words I wish I could say.”

With context provided from his grandmother’s autobiography, Nguyen was able to slowly piece together a lifetime through his grandmother’s words for the exhibition. He worked alongside a sense of loss to dive deeper into the forgotten stories of the past. “I learned a lot about what she’s gone through, and did in her life,” he began solemnly. “It’s just tough that I learned that, not from her saying it because she can’t remember it, but through her book.”

Upon moving to Canada in 2018, Nguyen’s yearning for his homeland stuck with him in all aspects of his work. Through his day-to-day tasks, he found joy in rediscovering what it meant to be a part of the Vietnamese diaspora. After seeking out the historical context on the atrocities of the Vietnam war and its greater implications, Nguyen grew curious of its effects within his own family. “And when I went back to Vietnam in the summer, I just wanted to ask them [his family] about it. I wanted to interview them and make a documentary.”

Similar to his past works, Nguyen attended to his creative outlets by keeping a visual diary of his grandmother during the crisp summer days in Vietnam. However, he was met with heartbreak in the process. “When I tried to interview my grandma or ask her questions, she would answer completely random things because she could not remember,” he explained. “So now I just had all this footage of her. All these photos I took of her when I was staying with her in her element living her life now.”

With no linear process for a final body of work, Nguyen later found himself writing poems that complemented the film materials. “I think I wanted to use the words for something as well,” he said. Later on, the film took less of a documentary approach, but rather a supplementary to the words he poured out in the poems. It began a grieving process for Nguyen, who had yet to process the eventual loss of his grandmother, and laid out the remainder of her life through his art.

Summer in Hanoi

Amidst the fast-paced city of Hanoi, Nguyen found serenity in the mundane lifestyles of those who resided. The sounds of motorcycles flooded the busy streets. Food stands selling popular Vietnamese street foods and loud conversations animated the city. However, walking amongst the walls of a welcoming home was one story out of millions meant to be told.

“I feel like there are so many different stories out there that we don’t know of. Especially in Vietnam, people who are living there right now have stories that are similar to my grandmother. Like she’s just one in a million, but her story is also just as special,” Nguyen explained.

Nguyen recalled back to his summer spent in his grandmother’s house. For over a month, he observed how she continuously made an effort to remember her life. Regardless of where her memory lied, she sought out the past. “What she would do is just read her book that she wrote every day. She would reread it again as if she was reading a new book every day because she was trying hard to remember, but the next day she would forget and repeat,” he revealed.

When faced with the realities of leaving Vietnam, Nguyen felt an overwhelming wave of homesickness. Looking back on his final moments with his grandmother, he recalled the agonizing moment of leaving her back home. “Basically, the last day I saw my grandma before I left to go abroad, her head was shaved and she looked really weak. She just looked entirely different from when I last saw her and I felt like that was the last time I was going to see her.”

On a flight returning back to Canada, he was met with the grief of leaving once again. “I didn’t know when the next time I could come back to Vietnam would be. I guess ever since that last moment I was down, I think that was the last time and now I had all this footage, but not any interview from her. So I journaled quite a lot about how I felt after the fact.”

The story of all immigrants remained an unspoken one, even for Nguyen himself. “I was just trying to say how I feel and all the words I couldn’t tell her. So I wrote it originally in English because that was now the language I felt most comfortable with,” he said. Nguyen would later form his thoughts into a poem and translate them to Vietnamese.

Opening “Hoa” to the Public

Attendees across school faculties filled the room in both curiosity and solidarity. Nervous for the reveal, Nguyen offered an all-encompassing Vietnamese experience on the opening night. After months of preparation, “Hoa” was finally set on display. On opposing sides of the room, Nguyen’s film and prose were projected to the viewers. The actual journal entries were set on display in Vietnamese while also heard from the speakers all around.

Worried that he might be misunderstood, Nguyen had hopes for “Hoa” to speak for itself. The curated space was “a lot more intimate than expected” according to the artist, but attendees were eager to take in the piece at their own pace. “I saw a lot of people just be able to unwind and just relax to be in a calm space and process all of this,” he expressed in relief.

The isolated setting, which gave visitors a chance to sit and observe the exhibition in all corners of the room, allowed all to step into Hanoi. “I felt so happy to universally connect with all these grieving feelings and to show that grief is such a universal feeling. Even when people tell me they’ve cried watching my film, it makes me feel happy as well,” he said. “Because I feel like those tears are probably tears of feeling. It’s a really sad project, but it’s really a hopeful one as well.”

Upon reflecting on the entirety of the exhibition, Nguyen felt hopeful for future Vietnamese generations. The rich history of Vietnam following the French colonization and the Vietnam war kept him encouraged to tell these stories. “Suffering is such a normal thing. Even with immigrants coming here, there is so much that they have gone through that young Vietnamese people will never know. So I just hope that we could appreciate it and think about our grandparents, I just feel like it’s so important.”

The line between culture and identity runs thin when it comes to concurring themes in Nguyen’s works. Seeing the two as one, he considered it to be a huge part of an ever-evolving identity even in the diaspora.

“I learned so much more and I just want the world to know about my culture too. The way I do that, I guess, is art, film, photography, and exhibitions.”

Looking for more coverage on art created by the Asian diaspora? Read our interview with Toronto- and Montreal-based artist Lan Florence Yee on their intimate works here.

This article is part of EnVi’s Gen Z issue. Order your physical copy here!